2.2 The Trait Approach to Leadership

During the early 1900s, scholars endeavored to understand leaders and leadership. They wanted to know, from an organizational perspective, what characteristics leaders hold in common in the hope that people with these characteristics could be identified, recruited, and placed in key organizational positions. This gave rise to early research efforts and to what is referred to as the trait approach to leadership. Prompted by the great man theory of leadership and the emerging interest in understanding what leadership is, researchers focused on the leader—Who is a leader? What are the distinguishing characteristics of the great and effective leaders? The great man theory of leadership holds that some people are born with a set of personal qualities that make truly great leaders. Mahatma Gandhi is often cited as a naturally great leader.

Leader Trait Research

Ralph Stogdill, while on the faculty at The Ohio State University, pioneered our modern (late 20th century) study of leadership.[1] Scholars taking the trait approach attempted to identify physiological (appearance, height, and weight), demographic (age, education, and socioeconomic background), personality (dominance, self-confidence, and aggressiveness), intellective (intelligence, decisiveness, judgment, and knowledge), task-related (achievement drive, initiative, and persistence), and social characteristics (sociability and cooperativeness) with leader emergence and leader effectiveness. After reviewing several hundred studies of leader traits, Stogdill in 1974 described the successful leader this way:

The [successful] leader is characterized by a strong drive for responsibility and task completion, vigor and persistence in pursuit of goals, venturesomeness and originality in problem solving, drive to exercise initiative in social situations, self-confidence and sense of personal identity, willingness to accept consequences of decision and action, readiness to absorb interpersonal stress, willingness to tolerate frustration and delay, ability to influence other person’s behavior, and capacity to structure social interaction systems to the purpose at hand.[2]

Looking at Trait Theory Today

So, if studying leadership traits isn’t useful, why are we talking about it? Well, surprisingly, interest in the topic continues, supported by media and general public opinion. Think about how media describes business leaders like Mary Barra and Bill Gates. They’re innovative. They make tough decisions. They’re philanthropic. The media is constantly throwing their personality traits out there for us to digest.

Twelve percent of all the research published on the topic of leadership between 1990 and 2004 contains the keywords “personality” and “leadership.” Interest persists, and new information has been uncovered. Researcher Steven J. Zaccaro pointed out that, even in Stogdill’s argument against traits, his studies contained conclusions suggesting that individual differences can still predict leader effectiveness.

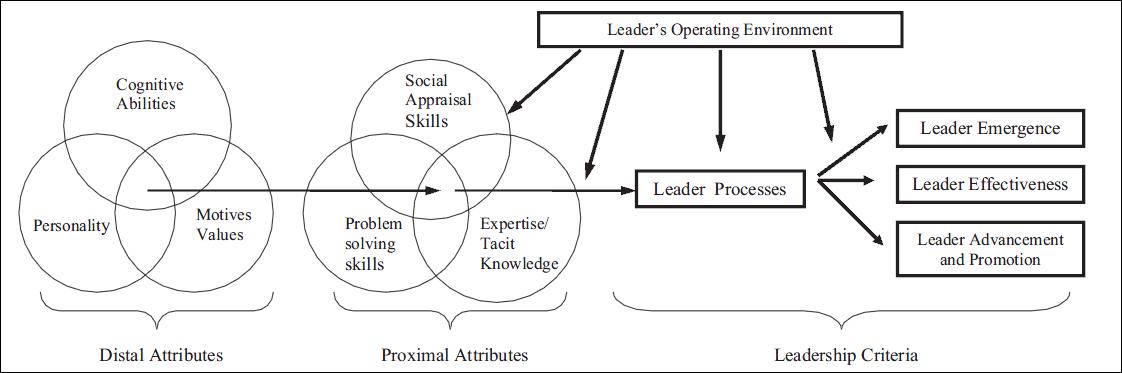

Remember that Cowley wrote that traits collectively lent themselves to leadership effectiveness. Taking a page from this book, Zaccaro and colleagues developed the trait-leadership model that attempted to address traits and their influence on a leader’s effectiveness. The premise of the Trait-Leadership Model (Zaccaro, Kemp, Bader, 2004) is that (a) leadership emerges from the combined influence of multiple traits (integrated, rather than individual, traits) and (b) leader traits differ in their proximal influence on leadership.

Zaccaro’s model looks like this:

This model comes with a list of leader traits, which Zaccaro reminds us are always not exhaustive. But traits based on his 2004 model include extraversion, agreeableness, openness, neuroticism, creativity, and others.

This model comes with a list of leader traits, which Zaccaro reminds us are always not exhaustive. But traits based on his 2004 model include extraversion, agreeableness, openness, neuroticism, creativity, and others.

Two other models have emerged in recent trait leadership studies. The Leader Trait Emergency Effectiveness Model, created by researcher Timothy Judge and colleagues, combines behavioral genetics and evolutionary psychology theories of how traits are developed and puts them into a model that attempts to explain leader emergence and effectiveness. A second model, the Integrated Model of Leader Traits, Behaviors, and Effectiveness, created by D. S. Derue and colleagues, combines traits and behaviors in predicting leader effectiveness and tested the mediation effect of leader behaviors on the relationship between leader traits and effectiveness.

In spite of the increased focus of researchers on trait theory, it remains among the more criticized theories of leadership. Some argue it’s too simplistic. Others criticize that it studies leadership effectiveness as it’s perceived by followers, rather than actual leadership effectiveness. But we want to leave you with two thoughts on the trait approach before we move on:

- Traits can predict leadership. Years ago the evidence suggested otherwise, but the presence of proper framework for classifying and organizing traits now help us understand this better.

- Traits do a better job of predicting the emergence of leaders and the appearance of leadership than they do distinguishing between effective and ineffective leadership.

Stogdill’s comments encouraged researchers to look in other directions back in the late 1940s. If it’s not the personality traits that predict effective leadership, perhaps it’s the behavior of those leaders we should be studying. Let’s take a look at the behavioral approach to leadership next.

The last three decades of the 20th century witnessed continued exploration of the relationship between traits and both leader emergence and leader effectiveness. Edwin Locke from the University of Maryland and a number of his research associates, in their recent review of the trait research, observed that successful leaders possess a set of core characteristics that are different from those of other people.[3] Although these core traits do not solely determine whether a person will be a leader—or a successful leader—they are seen as preconditions that endow people with leadership potential. Among the core traits identified are:

- Drive—a high level of effort, including a strong desire for achievement as well as high levels of ambition, energy, tenacity, and initiative

- Leadership motivation—an intense desire to lead others

- Honesty and integrity—a commitment to the truth (nondeceit), where word and deed correspond

- Self-confidence—an assurance in one’s self, one’s ideas, and one’s ability

- Cognitive ability—conceptually skilled, capable of exercising good judgment, having strong analytical abilities, possessing the capacity to think strategically and multidimensionally

- Knowledge of the business—a high degree of understanding of the company, industry, and technical matters

- Other traits—charisma, creativity/originality, and flexibility/adaptiveness[4]

While leaders may be “people with the right stuff,” effective leadership requires more than simply possessing the correct set of motives and traits. Knowledge, skills, ability, vision, strategy, and effective vision implementation are all necessary for the person who has the “right stuff” to realize their leadership potential. [5]According to Locke, people endowed with these traits engage in behaviors that are associated with leadership. As followers, people are attracted to and inclined to follow individuals who display, for example, honesty and integrity, self-confidence, and the motivation to lead.

Personality psychologists remind us that behavior is a result of an interaction between the person and the situation—that is, Behavior = f [(Person) (Situation)]. To this, psychologist Walter Mischel adds the important observation that personality tends to get expressed through an individual’s behavior in “weak” situations and to be suppressed in “strong” situations.[6] A strong situation is one with strong behavioral norms and rules, strong incentives, clear expectations, and rewards for a particular behavior. Our characterization of the mechanistic organization with its well-defined hierarchy of authority, jobs, and standard operating procedures exemplifies a strong situation. The organic social system exemplifies a weak situation. From a leadership perspective, a person’s traits play a stronger role in their leader behavior and ultimately leader effectiveness when the situation permits the expression of their disposition. Thus, personality traits prominently shape leader behavior in weak situations.

Finally, about the validity of the “great person approach to leadership”: Evidence accumulated to date does not provide a strong base of support for the notion that leaders are born. Yet, the study of twins at the University of Minnesota leaves open the possibility that part of the answer might be found in our genes. Many personality traits and vocational interests (which might be related to one’s interest in assuming responsibility for others and the motivation to lead) have been found to be related to our “genetic dispositions” as well as to our life experiences.[7] Each core trait recently identified by Locke and his associates traces a significant part of its existence to life experiences. Thus, a person is not born with self-confidence. Self-confidence is developed, honesty and integrity are a matter of personal choice, motivation to lead comes from within the individual and is within his control, and knowledge of the business can be acquired. While cognitive ability does in part find its origin in the genes, it still needs to be developed. Finally, drive, as a dispositional trait, may also have a genetic component, but it too can be self- and other-encouraged. It goes without saying that none of these ingredients are acquired overnight.

Other Leader Traits

Sex and gender, disposition, and self-monitoring also play an important role in leader emergence and leader style.

Sex and Gender Role

Much research has gone into understanding the role of sex and gender in leadership.[8] Two major avenues have been explored: sex and gender roles in relation to leader emergence, and whether style differences exist across the sexes.

Evidence supports the observation that men emerge as leaders more frequently than women.[9] Throughout history, few women have been in positions where they could develop or exercise leadership behaviors. In contemporary society, being perceived as experts appears to play an important role in the emergence of women as leaders. Yet, gender role is more predictive than sex. Individuals with “masculine” (for example, assertive, aggressive, competitive, willing to take a stand) as opposed to “feminine” (cheerful, affectionate, sympathetic, gentle) characteristics are more likely to emerge in leadership roles.[10] In our society males are frequently socialized to possess the masculine characteristics, while females are more frequently socialized to possess the feminine characteristics.

Recent evidence, however, suggests that individuals who are androgynous (that is, who simultaneously possess both masculine and feminine characteristics) are as likely to emerge in leadership roles as individuals with only masculine characteristics. This suggests that possessing feminine qualities does not distract from the attractiveness of the individual as a leader.[11]

With regard to leadership style, researchers have looked to see if male-female differences exist in task and interpersonal styles, and whether or not differences exist in how autocratic or democratic men and women are. The answer is, when it comes to interpersonal versus task orientation, differences between men and women appear to be marginal. Women are somewhat more concerned with meeting the group’s interpersonal needs, while men are somewhat more concerned with meeting the group’s task needs. Big differences emerge in terms of democratic versus autocratic leadership styles. Men tend to be more autocratic or directive, while women are more likely to adopt a more democratic/participative leadership style.[12] In fact, it may be because men are more directive that they are seen as key to goal attainment and they are turned to more often as leaders.[13]

Dispositional Trait

Psychologists often use the terms disposition and mood to describe and differentiate people. Individuals characterized by a positive affective state exhibit a mood that is active, strong, excited, enthusiastic, peppy, and elated. A leader with this mood state exudes an air of confidence and optimism and is seen as enjoying work-related activities.

Recent work conducted at the University of California-Berkeley demonstrates that leaders (managers) with positive affectivity (a positive mood state) tend to be more competent interpersonally, to contribute more to group activities, and to be able to function more effectively in their leadership role.[14] Their enthusiasm and high energy levels appear to be infectious, transferring from leader to followers. Thus, such leaders promote group cohesiveness and productivity. This mood state is also associated with low levels of group turnover and is positively associated with followers who engage in acts of good group citizenship.[15]

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring as a personality trait refers to the strength of an individual’s ability and willingness to read verbal and nonverbal cues and to alter one’s behavior so as to manage the presentation of the self and the images that others form of the individual. “High self-monitors” are particularly astute at reading social cues and regulating their self-presentation to fit a particular situation. “Low self-monitors” are less sensitive to social cues; they may either lack motivation or lack the ability to manage how they come across to others.

Some evidence supports the position that high self-monitors emerge more often as leaders. In addition, they appear to exert more influence on group decisions and initiate more structure than low self-monitors. Perhaps high self-monitors emerge as leaders because in group interaction they are the individuals who attempt to organize the group and provide it with the structure needed to move the group toward goal attainment.[16]

Note on Attribution

Chapter 2.2 The Trait Approach to Leadership was adapted from the following openly licensed materials:

“Chapter 12.4, The Trait Approach to Leadership – Organizational Behavior” by J. Stewart Black and David S. Bright, OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/1-introduction.

“The History of Leadership Theories” by Lumen Learning, licensed under CC BY 4.0. (Looking at Trait Theory Today section)

- Stogdill, 1948; R. M. Stogdill. 1974. Handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research. New York: Free Press. ↵

- Ibid., 81. See also Stogdill, 1948. ↵

- S.A. Kirkpatrick & E.A. Locke. 1991. Leadership: Do traits matter? The Executive 5(2):48–60. E.A. Locke, S. Kirkpatrick, J.K. Wheeler, J. Schneider, K. Niles, H. Goldstein, K. Welsh, & D.-O. Chad. 1991. The essence of leadership: The four keys to leading successfully. New York: Lexington. ↵

- Kirkpatrick & Locke. 1991. The best managers: What it takes. 2000 (Jan. 10). Business Week, 158. ↵

- Locke et al., 1991; T.A. Stewart. 1999 (Oct. 11). Have you got what it takes? Fortune 140(7):318–322. ↵

- W. Mischel. 1973. Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review 80:252– 283. ↵

- R.J. House & R.N. Aditya. 1997. The social scientific study of leadership: Quo vadis? Journal of Management 23:409– 473; T.J. Bouchard, Jr., D.T. Lykken, M. McGue, N.L. Segal, & A. Tellegen. 1990. Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota study of twins reared apart. Science 250:223–228. ↵

- S. Helgesen. 1990. The female advantage. New York: Doubleday/Currency; J. Fierman. 1990 (Dec. 17). Do women manage differently? Fortune 122:115–120; J.B. Rosener. 1990 (Nov.–Dec.). Ways women lead. Harvard Business Review 68(6): 119–125. ↵

- J.B. Chapman. 1975. Comparison of male and female leadership styles. Academy of Management Journal 18:645–650; E.A. Fagenson 1990. Perceived masculine and feminine attributes examined as a function of individual’s sex and level in the organizational power hierarchy: A test of four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology 75:204–211. ↵

- R.L. Kent & S.E. Moss. 1994. Effects of sex and gender role on leader emergence. Academy of Management Journal 37: 1335–1346. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- A.H. Early & B.T. Johnson. 1990. Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 108:233–256. ↵

- G.H. Dobbins, W.S. Long, E. Dedrick, & T.C. Clemons. 1990. The role of self-monitoring and gender on leader emergence: A laboratory and field study. Journal of Management 16:609–618. ↵

- B.M. Staw & S.G. Barsade. 1993. Affect and managerial performance: A test of the sadder-but-wiser vs happier-and-smarter hypothesis. Administrative Science Quarterly 38:304–331. ↵

- J.M. George & K. Bellenhausen. 1990. Understanding prosocial behavior, sales performance, and turnover: A group-level analysis in a service context. Journal of Applied Psychology 75:698–709. ↵

- Dobbins et al., 1990. ↵